In the southern Baltics a vast landscape of Pleistocene origin stretches from northern Germany, throughout Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, toward Estonia. Stagnant inland waters, such as lakes, ponds, bogs etc. are an indispensable part of this landscape. These waters, since their very existence, are the habitat of stoneworts and humans.

Stoneworts are winter-green fresh-water macrophytes[1]. They form meadows on the shallow bottoms of lakes, ponds and streams where the light reaches the ground and where the water is clear. Stoneworts are inconspicuous to us, because they are not very large and barely reach the water surface where they grow. In the Encyclopedia Britannica is written: „Stoneworts are of little direct importance to humans.“[2] I would like to question this statement.

Photo: Stonewort meadow and perches in December 2024 at Lake Niedzięgiel, Poland

I grew up on the shores of one of these stonewort-lakes, at Lake Stechlin, in northern Germany in the 1970s. It is true, I barely noticed the meadows. In summer, while swimming in the lake, I stepped through their soft ground, watched the perches, who found hiding places among their delicate branches.

Photo: Boy watching fish in the shallow, clear water at Lake Stechlin, August 2024

But I did not waste a thought on them. I had no name for them. By that time, I already knew their scientific family name, the Charales. At university I learned that they produce limy spore capsules (i.e., oospores), which are ornamented with a beautiful spiral pattern, which can be found as fossils. In fact, the oldest of these fossilized so called “gyrogonites”, are more than 400 million years old[3]. Charales have been around since a long time. Not so much at Lake Stechlin anymore.

In 2020, during the COVID-summer, when I spend some weeks at the lake, I noticed something disturbing. I couldn’t really say what it was. The lake had changed its appearance; a subtle change in color of its water, a strange overgrowth on the pebbles, small twigs, and even the sand by a hairy film of fine filamentous green algae. The once spectacular clear water was not spectacular clear anymore. This was the beginning of my enquiry and engagement with the fate of the lake, which holds until today. Among other things I learned that scientific mapping of the lake bottom revealed that the once widespread meadows of stonewort are gone at Lake Stechlin.[4] Instead, thick layers of filamentous green algae cover the ground where the light reaches and massive floating thickets of hornwort (Ceratophyllum demersum) flourish during the summer season.[5]

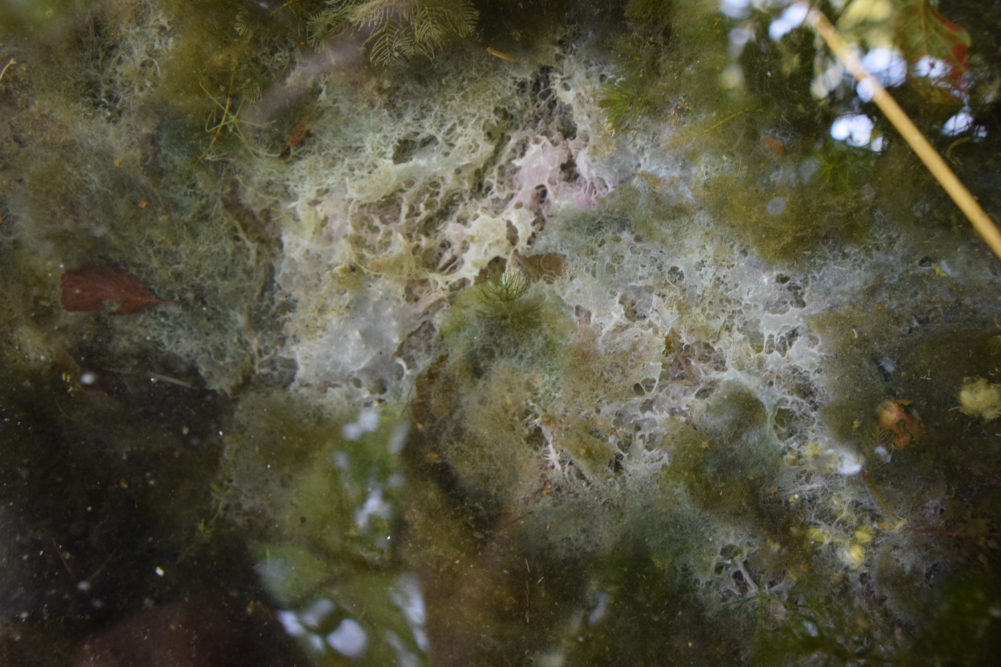

Photo: Fouling masses of aquatic macrophytes in shallow water of Lake Stechlin, Germany, August 2024

Photo: Accumulation of masses of floating hornwort (Ceratophyllum demersum) and filamentous green algae near the shore of Lake Stechlin, August, 2024.

I live in Finland now, thousands of kilometers away from the lake. My daily business, I work as a paleontologist at the Finnish Museum of Natural History, involves for large parts research on how aquatic ecosystems change at geological time scales, ecosystems which are hundreds of millions of years old. How would I be able to integrate, what I know from my paleontological science, to become relevant to changes of ecosystems of today. Ecosystems even, to which I have a personal relationship, to which I, to a certain extent, belong? And, also, the other way around; how could, what I learn from the lake become relevant for my paleontological research?

From a friend then, by chance I got to know that in Oulu, Finland, they ran an interdisciplinary scientific program named “Biodiverse Anthropocenes”[6]. And there a social anthropologist, Małgorzata Zofia Kowalska, had a fellowship with a focus on stonewort in Poland. I quickly learned that she also has a personal relationship to these organisms. She spends her summers together with her family at Lake Niedzięgiel near Poznań, central Poland.

We became engaged in a fascinating email-conversation about lake ecosystems, people’s relations to the lakes and their hidden underwater plants, and about the challenges to understand the relations within and around the lakes at timescales from geologic to seasonal. The Rewilding Culture project gave us the possibilty to meet. We met at Lake Stechlin in early August and at Lake Niedzięgiel in early December. Stonewort is winter green, so I saw its meadows in the lake in December. But at the same time, what a sight: the lake’s water level has dropped dramatically in recent years, as it has in so many lakes in the region, in Poland and in Germany.[7] This is the latest the Anthropocene-signature of this region: shorelines with piers standing in the dry. Belts of young alders and willows surround the lakes where just a few years ago perches swam.

Photo: Piers standing in the dry at beach of Skorzęcin, Lake Niedzięgiel, Poland, Dezember, 2024

Photo: “Jumping in the water forbidden” at beach of Skorzęcin, Lake Niedzięgiel, Poland, Dezember, 2024

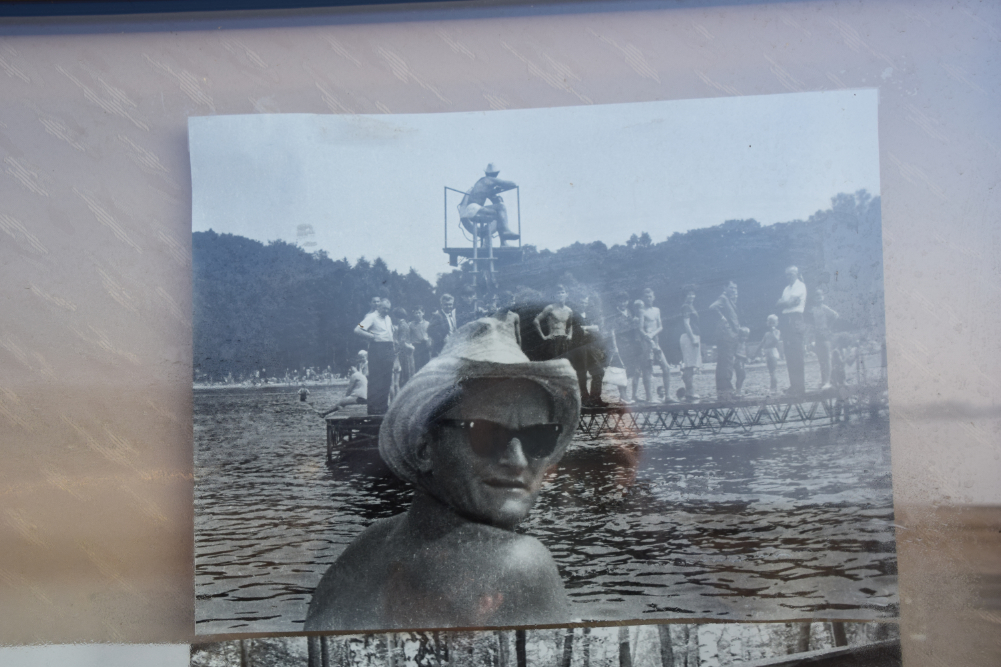

Photo: Historical photo displayed in one of the beach cafés at Skorzęcin, Lake Niedzięgiel, Poland showing the water level in the 1970s.

Photo: Dry pier at Lake Powidzkie, Poland, Dezember, 2024

Conversation at Leddernbrück, Lake Stechlin, Germany, August 2024

Małgorzata brought his son to Stechlin, and he had fun swimming in the lakes nearby during hot summer days, as if nothing happened. At Stechlin we met with conservationists and researchers, in Poznan we had a seminar at her institute at the Adam Mickiewicz University, where hydrobiologists had the chance to discuss with scholars of the humanities and with a paleontologist about the memory of a lake. These kinds of meetings are rare occasions, where we could start thinking about the relevance of our sciences for the stonewort in the lakes we relate to and, the other way around, the relevance of stonewort for these disciplines and us.

Stonewort is in several ways a remarkable organism: It represents the group of algae from which land plants evolved some 450 million years ago.[8] It is a type of organism queering the boundaries of what the common understanding of algae and a plant is. Stonewort species can be at the same time be threatened and invasive species.[9] Their oospores can form seed banks at the bottom of lakes and bogs and survive for hundreds of years.[10] They may belong to the ecological memory of a lake. And finally, it is known that stonewort plays an important role to keep the water bodies livable, in which it grows.[11]

It took me these four years, since the COVID summer, to understand that the colour change of the Stechlinsee was related to the disappearance of the stoneworts. Stoneworts purify the water; their light meadows are green all year round. It is the shiny lime they produce on their fragile branches that brightens the shallow ground where they grow. What the Stechlin lacks is the colour of the stonewort, a colour that has been present in inland water bodies this postglacial landscape for hundreds of millions of years. People should notice it. We should ask ourselves how to live with stonewort.

Björn Kröger

Rewilding Cultures mobility grantee 2024 on the behalf of Radiona.org

December 6th 2024, Helsinki

[1] The term “macrophytes” commonly used as a wrapper to include all kinds of aquatic vegetation that is larger then microscopic, including large algae, mosses, stoneworts, and vascular plants.

[2] https://www.britannica.com/science/stonewort

[3] Soulié-Märsche, I., & García, A. (2015). Gyrogonites and oospores, complementary viewpoints to improve the study of the charophytes (Charales). Aquatic botany, 120, 7-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2014.06.003

[4] Van de Weyer, K., Päzolt, J., Tigges, P. A. T. R. I. C. K., Raape, C., & Oldorff, S. (2009). Flächenbilanzierungen submerser Pflanzenbestände—Dargestellt am Beispiel des Großen Stechlinsees (Brandenburg) im Zeitraum von 1962–2008. Naturschutz Landschaftspfl. Brand, 18, 1-6.

[5] Gonsiorczyk, T., Hupfer, M., Hilt, S., & Gessner, M. O. (2024). Rapid Eutrophication of a Clearwater Lake: Trends and Potential Causes Inferred From Phosphorus Mass Balance Analyses. Global Change Biology, 30(11), e17575. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.17575

[6] https://www.oulu.fi/en/research/biodiverse-arctic-and-global-resilience/biodiverse-anthropocenes

[7] https://www.lebensraumwasser.com/weltweites-seen-sterben-auch-brandenburg-ist-betroffen/

[8] Karol, K. G., McCourt, R. M., Cimino, M. T., & Delwiche, C. F. (2001). The closest living relatives of land plants. Science, 294(5550), 2351-2353. DOI: 10.1126/science.1065156

[9] Larkin, D. J., Monfils, A. K., Boissezon, A., Sleith, R. S., Skawinski, P. M., Welling, C. H., ... & Karol, K. G. (2018). Biology, ecology, and management of starry stonewort (Nitellopsis obtusa; Characeae): A Red-listed Eurasian green alga invasive in North America. Aquatic Botany, 148, 15-24.

[10] Stobbe, A., Gregor, T., & Röpke, A. (2014). Long-lived banks of oospores in lake sediments from the Trans-Urals (Russia) indicated by germination in over 300 years old radiocarbon dated sediments. Aquatic Botany, 119, 84-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2014.07.004

[11] Pukacz, A., Asaeda, T., Blindow, I., Bueno, N. C., Casanova, M. T., Herbst, A., ... & Schubert, H. (2024). Ecology of Charophytes: Niche Dimensions of Pioneers and Habitat Engineers. Charophytes of Europe, 125-152.